Burned out, demoralized, anxious, and exhausted – these are just a few terms that have been used to describe both teachers and leaders as they head into a new school year.

At The Learning Accelerator (TLA), we saw this issue emerging over a year ago. To surface potential strategies and solutions, we conducted a review of over 60 pieces of literature as well as a focus group and interviews with diverse leaders from across the country. These efforts uncovered a host of concrete strategies and resulted in the creation of a framework to help educators, leaders, and policymakers have concrete and actionable conversations about the wellbeing of the adults in their communities.

Beyond anecdotal evidence, the results of a survey conducted in January 2022 by the National Education Association (NEA) paints an even more bleak picture. Approximately 90% of the respondents reported burnout as a serious issue, and 55% indicated that they were considering either retiring early or leaving the profession altogether. Last June, an analysis from AFT and Hart Research Associates found a 34-point increase in teacher dissatisfaction since the start of the pandemic with workloads, working conditions, constant disruptions, and varying levels of support listed as contributing factors. More recently, an EdDive Brief identified politicians, parents, policy debates, and increasing curriculum restrictions as new sources of stress for teachers coming back to school.

This problem is not contained to just teachers. A recent report from RAND found that this problem also extends to school leaders. Secondary principals reported that attending to the wellbeing of the adults and students in their community has markedly contributed to their feelings of stress; and The School Superintendents Association (AASA) reported that 186 of the 500 largest districts in the country have experienced some level of superintendent turnover since the start of the pandemic.

While adult wellbeing and attrition are not new problems, the challenges of the last few years have intensified pressures on educators and leaders. As a result, leaders and policymakers have sought out immediate solutions ranging from professional development focused on self-care, to mindfulness and yoga, to mental health days. However, these initiatives often fall flat, focusing on the symptoms rather than the underlying problem.

Start with the Four Drivers of Wellbeing

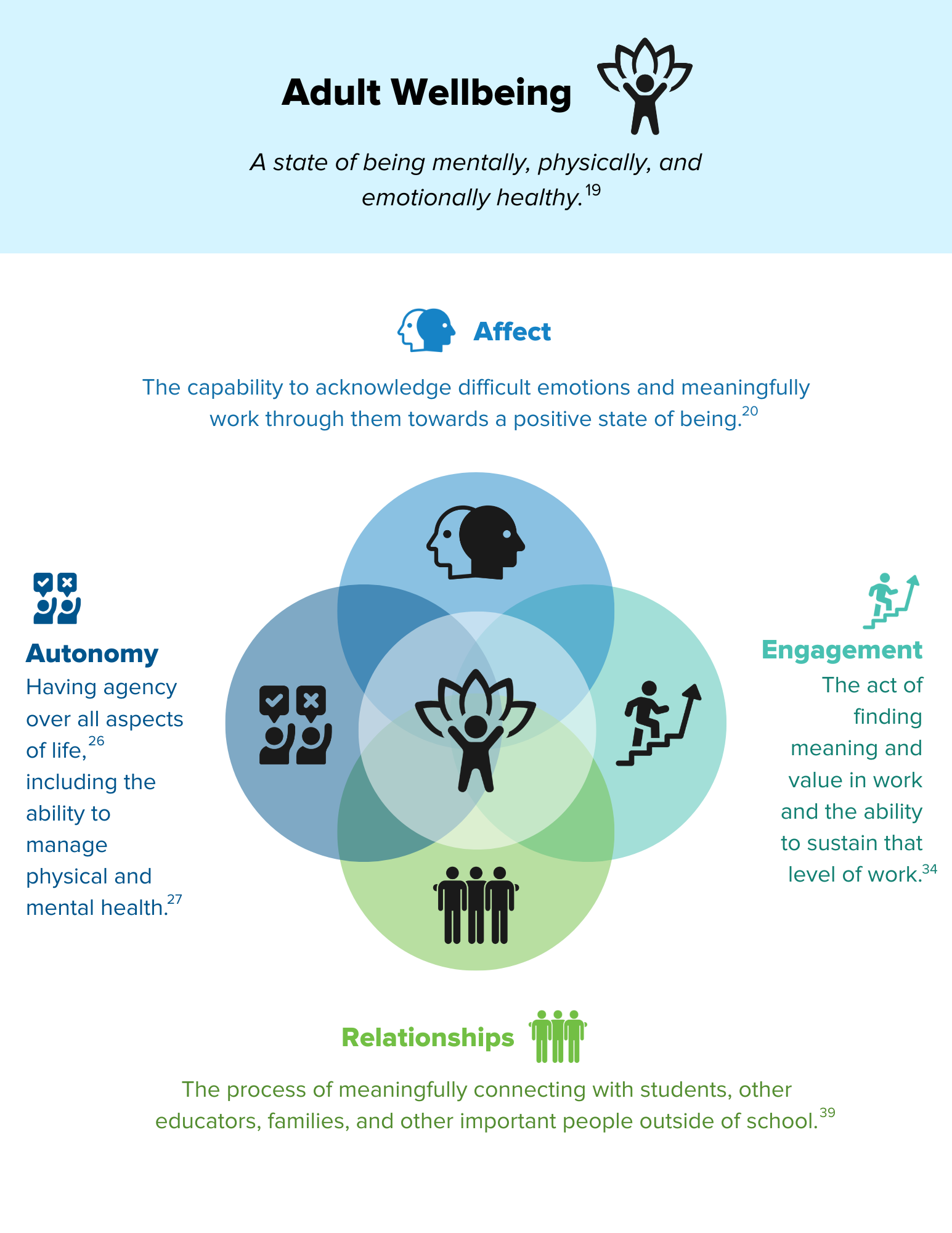

We define adult wellbeing as the state of being emotionally, physically, and mentally healthy. To achieve this state requires attention to four interrelated drivers:

-

Affect: The ability to name emotions and work through them. Many educators have described negative feelings such as difficulty focusing or a sense of “drowning” due to the precarious state of the world.

- Autonomy: A person’s potential to take agency over all aspects of their life, including their time, working environment, and health. During remote learning, many educators reported an increased sense of autonomy as they had more control over their daily schedules; however, since returning to in-person schooling, that freedom has been usurped by additional meetings and responsibilities.

-

Engagement: An individual’s ability to find meaning and value in their daily work as well as have the capacity to sustain that work, essentially avoiding burnout. Teaching has long been considered a profession of “moral rewards.” Educators find value in working with their students. With increasing workload, public criticism, and the stress of coping with students mental and behavioral needs, many no longer find the work sustainable.

-

Relationships: The act of meaningfully connecting and collaborating with others. Both teachers and leaders found it difficult to maintain meaningful relationships with students as well as colleagues when in an online setting.

Unfortunately, many educators and leaders have faced challenges to nearly every driver of wellbeing. While individualistic strategies such as mindfulness, yoga, and self-care can be well-intentioned, they are often presented as supports to one driver (i.e., affect or relationships) but at the expense of another, especially autonomy. Instead, we found that initiatives need to be designed with the drivers in mind.

For example, Austin ISD addressed teachers’ wellbeing by implementing remote cross-district collaborative planning. Not only did this make teachers’ workloads more sustainable, increasing engagement, but it also allowed them to foster stronger relationships with their colleagues. Because planning sessions occurred during regular work hours, teachers viewed it as beneficial and not a threat to their time and autonomy.

Sustaining Adult Wellbeing in Schools and Districts

Now more than ever, leaders and policymakers need to address the wellbeing of the adults within their school or district community. Potential strategies span a continuum from short-term, individual wins to longer-term, community-level solutions. However, these changes only become sustainable when the onus for care transitions away from a single leader and towards the collective community.

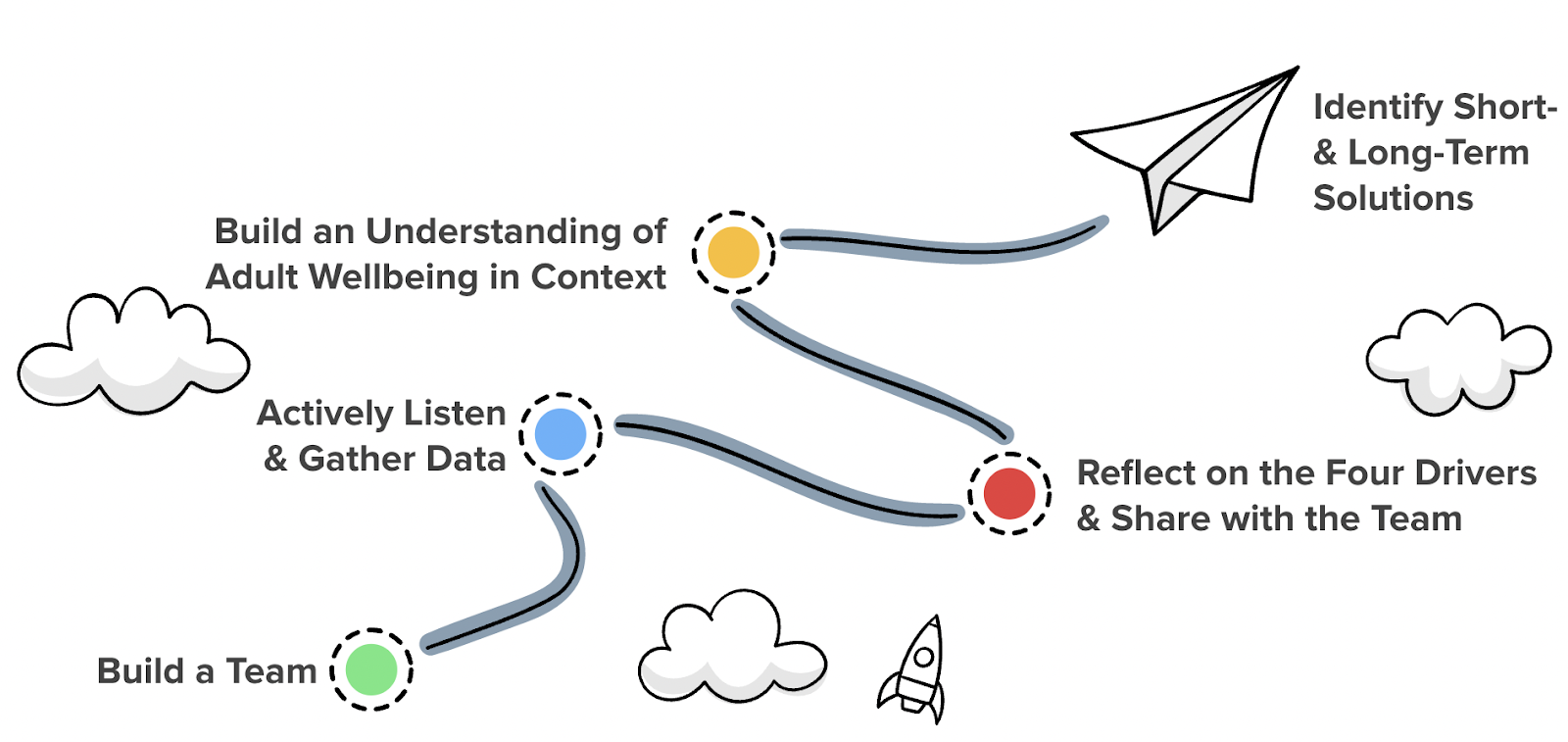

Although no single solution exists, and not every suggestion will work, schools and districts need to identify strategies that can be successful within their unique contexts. To do this, we identified four areas for action:

-

Actively listen to what adults need. Whether through surveys, polls, interviews, or conversations, begin by asking what adults need and then openly discuss what may be feasible to implement. We have two openly available surveys on our web site.

-

Meet immediate, individual needs. While it can be tempting to focus on quick interventions such as pizza parties or mindfulness sessions, the underlying drivers of adult wellbeing need to be addressed and strategies should take them into account.

-

Invest in long-term supports. Community-based strategies such as distributed leadership or collaborative decision making take longer to implement, but they can help leaders build a sustained culture of care over time.

-

Build an ongoing culture of care. Transforming a school or district’s culture of adult wellbeing requires consistent, systems-level change where the responsibility for care shifts from an individual leader to the collective.

The past two years have challenged educators and leaders in unimaginable ways. And yet, they have also increased awareness about the importance of adult wellbeing in schools. We believe that by leveraging the four drivers to have concrete and actionable conversations, the resulting systemic changes will ultimately benefit everyone in the community.