This blog was originally published on the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center Chalkboard.

When 80 million Facebook users’ data were found to be in the hands of Cambridge Analytica, users of the social media platform–and Congress–decided it was time to take a closer look at the data collected by the platform and the apps it hosts. I couldn’t help but draw a parallel to the 50 million public students across the nation whose data are similarly collected and shared by and among numerous entities including (as in the Facebook case) researchers and third-party developers.

Educational data are routinely used in schools for a variety of purposes, such as accountability reporting, planning, communications, and personalizing learning for students. When the right stakeholders have access to the right data at the right time, students benefit. However, we need to be careful–more careful than we have been–to ensure that our students’ privacy is protected and their data are used for good.

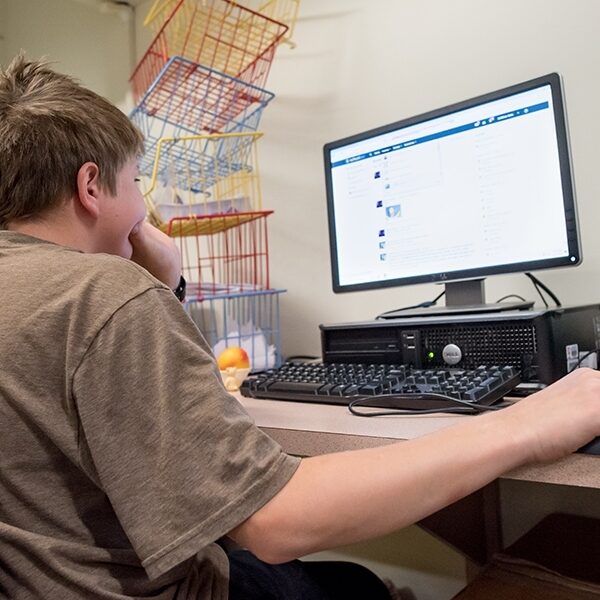

Today, most if not all students in public and other school systems across the country have some form of data about themselves and their academic progress collected and stored. In 2017, 72 percent of teachers reported using educational data for instructional purposes, and 62 percent of administrators identified data use as a priority for professional development in their district. This information is virtually all collected and/or stored electronically. In 2015, over $13 billion was spent by school districts on ed tech, and as ed tech proliferates, the number and type of agencies that have access to those data only grows. The students in your own life probably have multiple pieces of educational data stored in multiple places, regardless of the community that you live in or the schools they attend–and if they don’t currently, they certainly will in the near future.

The primary relevance Facebook data have to educational data is the matter of stewardship. Many individuals in a variety of roles are given the responsibility of “protecting” data (and thereby students’ privacy), but few are actually given any authority, much less incentive and support, to do so. In the case of student data, there are three primary stewards of educational data, depending on the specific context in which those data are being collected and used.

- The school system (or systems) in which the student is enrolled are primary data stewards.

- If students or educators use ed tech, then developers, often housed within publishing companies or vendors, are “secondary” stewards of some educational data.

- If students are participating in any research, evaluation, or measurement activities, researchers along with research institutions (in most cases) can also be secondary stewards of some educational data.

As we saw with the Facebook data, having multiple groups responsible for protecting individuals’ data and privacy can, in fact, lead to a situation where no group is sufficiently alert to how data are being shared and used. In other words, misuse of data is unlikely to be detected because each group trusts the other group(s) to be vigilant, so that no group is routinely and regularly checking who has what data and how they are being used.

Several federal laws govern the use and sharing of educational data: FERPA, HIPAA (in the case of data about disabilities), COPPA, and PPRA. The primary problem lies in the enactment and enforcement (or lack thereof) of these laws. Many folks who fall under the jurisdiction of these laws are not aware that they should be following them or don’t know what the laws require, and all too often the laws are not enforced. Moreover, while these laws (FERPA in particular) provide critical, necessary, and basic protections to students, they do not go as far as one would reasonably assume. There are misuses of educational data and data sharing that may be considered unethical that are perfectly legal. For example, a company could use educational data that it legitimately collected as part of instruction to target marketing of services or other apps to particular students, schools, or districts.

Fortunately, there are ethical guidelines–such as requiring data collection from students to be for the purpose of improving learning–for collecting and storing any data from individuals for research purposes. These guidelines are administered through Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). These guidelines work in tandem with protective practices that researchers routinely use to safeguard data privacy. These practices include working only with data that have been stripped of personally identifying information (like names or dates of birth), not including groups of individuals who have unique enough information that make their data identifiable (e.g., those from a very uncommon ethnic group), and storing both signed consent forms and data in secured (digital and physical) locations, but separately from each other.

Unfortunately, there are many other purposes for data use that IRBs would not rationally apply to, and these uses do not have nearly as much of an established code of ethics for use. Further, IRBs do not (and are not required to) exist at every entity that conducts research, nor are they used by everyone conducting educational research. Like the laws, enforcement of ethical guidelines is also weak and left only up to the willing to serve as enforcers. Some academic journals and funders of educational research will require their grantees to certify that any data collection they fund is conducted with IRB approval. Occasionally, districts and agencies providing the data will require IRB approval. By and large, the ethical use of educational data is not legislated, and is generally left to up an “honor code.”

I view the Facebook data situation as a wake-up call for all of us who generate, collect, store, or use student data. While I know the vast majority of us are using these data for good, the fact is the systems we have and are developing around these data can be used for the opposite. Relying on Congress to hold more hearings, or even pass new laws, is not enough. It is our responsibility, within our roles as parents and families, educators, administrators, researchers, and policymakers to balance availability with vigilance of our students’ data. We need to educate ourselves about the rights and the responsibilities we have to protect students. Some of these responsibilities, like parents asking your school leaders how educational data are used and shared, or state policymakers establishing roles for data stewardship, are outlined at the previous links.

Educational data use is here to stay, and is in fact a potentially powerful tool in closing achievement gaps through truly equitable learning experiences. To benefit from this reality, rather than be hurt by it, let us step up and become better stewards of our students’ data and their privacy. If we don’t, Facebook has shown us how others could step in and take advantage.