This piece was originally posted on EdSurge.

We must either: integrate technology or support teachers; teach traditionally or personalize learning; support districts or support charters; fund edtech or fund schools; individualize learning or humanize instruction.

As oversimplified as the above statements may seem, recent public discourse around ongoing trends in K-12 education has fallen into this trap of two-sided, black-and-white debates. Too often, education leaders pit one perspective against another, creating false dichotomies that do more harm than good. While a healthy level of criticism and discussion are important to any new idea, especially when it pertains to the future of our youth, the field of education would benefit from understanding the complex nuances and intersections of every perspective, rather than simply choosing one side over another.

We need to collectively shift from either/or thinking to both/and thinking.

This binary approach has been especially pervasive in the debate over personalized learning. As the movement grows, skeptics have vocalized concerns that aim to polarize opinions, especially with the use of technology in classrooms. However, we must recognize that either side in these false dichotomies (e.g., teachers vs. technology, individualization vs. humanization, etc.) is not sufficient to serving our students best. As a former classroom educator, I’ve found that the intersections at which “opposing” sides actually align are where we’ll discover the best solutions for our classrooms.

Technology empowers teachers to be effective and sustainable.

Most will agree that technology cannot and will not replace the role of a teacher, and we should never strive for that outcome. However, that does not mean classrooms must be void of technology in order to preserve the impact of teachers. Rather, strategic integration of technology can empower a teacher to do more while being efficient. Whether it’s capturing evidence of student learning and sharing with families, grading student assessments, sharing feedback on student writing, or assigning individualized practice, teachers utilize technology as one of many tools in their toolkit for being effective.

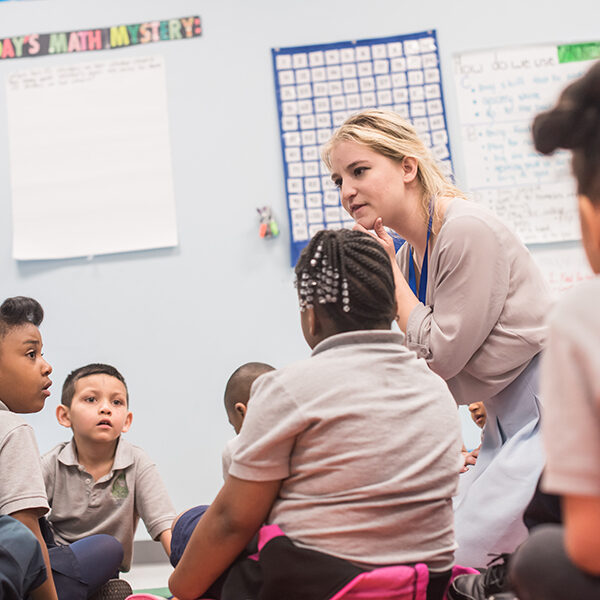

Classrooms can leverage technology to support student collaboration and discourse.

Understandably, there is concern about the overuse of technology and the amount of screentime in schools. But let’s not simplify time spent with technology to only individualized, low-level consumption of content, and, conversely, time without technology to effective learning.

Instead, we should scrutinize the quality and rigor of student learning throughout the entire school day, whether it involves technology or not. Thoughtfully integrated technology can support creative problem solving and critical thinking applications, both individually and among groups of learners. Just as technology has connected global communities, it can spark and facilitate connections in classrooms, allowing students to dynamically use technology and collaborate with peers.

Personalized learning is really just an extension of good teaching.

A consistent narrative has emerged that pits personalized learning against the human side of learning. But if we strip modern day personalized classrooms of technology, we’d find the same principles from Maria Montessori’s movement from the early 1900s. Good teachers, regardless of the time period or tools available, want to support each student based on his or her individual needs and develop students into self-directed learners. Integrating technology and these principles allow schools to scale these practices and make it more sustainable for educators to be effective.

Overly broad critiques of technology integration undermine the professionalism of educators.

Ultimately, those that suffer most from these divisive debates are educators. When we make broad either/or statements about what is good or bad in classrooms, especially without clear evidence, we risk over-generalizing the contexts and needs of every classroom and discounting the professionalism and ability of educators to make decisions on what is best for their classrooms and students.

Instead of forcing the field to coalesce around one side or another, we must better examine the nuances of the various approaches and garner evidence where possible, allowing educators – as professionals – to make informed decisions and best design instruction within their classrooms.

Transforming our current day classrooms and schools to give every child the quality education they deserve is crucial. If we continue the trend of either/or thinking, we’ll only stunt our progress and risk regressing in this imperative. We must shift to both/and thinking, pulling strengths from all approaches and perspectives, if we want to ensure success for all students.