This blog first appeared on EdWeek’s Next Gen Learning in Action column.

At Silicon Schools Fund we invest in schools that take new approaches to education. We recently wrote that many schools are starting to create flex time periods during the day, where students work independently, often online, while teachers perform high-leverage activities such as student mentoring and small-group instruction. For flex time to work well, schools have to accomplish a tricky balance between fostering autonomy in students while still holding them accountable for ambitious learning targets.

Together with Relay Graduate School of Education, we observed eight examples of flex time in schools, utilizing a data collection tool and protocol. We interviewed teachers, administrators, and students. We entered with hypotheses about what makes flex time effective and several learnings emerged including:

- Strong structures ultimately create more student autonomy. Classrooms that are initially teacher-driven can gradually turn responsibility over to students while still ensuring that time is used effectively.

- In the best classrooms, teachers are purposeful in their planning, students are clear on the norms, and expectations are continuously reinforced.

- Data should be transparent to teachers and students and used by both to effectively set goals and make instructional decisions for and by students.

To better understand what these ideas looks like in practice, we highlight below three different examples of schools that are using flex time well. Each of these schools exhibit the above learnings in different ways.

Summit Shasta

Upon first glance Personalized Learning Time (PLT) at Summit Shasta may appear to be simply a high-tech study hall. Twenty-six ninth-graders sit two to three students per table, laptops open and notebooks or other kinds of graphic organizers out, mostly working independently on assignments of their own choosing from a playlist on the Summit Learning Platform or a related project. A quiet hum of collaboration permeates the classroom as some students turn to a neighbor for insights into a problem they’ve just encountered, or to chat during a brief study break. Others appear deep in their own work, earbuds protecting them from noise and distractions. This simple appearance of a glorified study hall masks a complex set of expectations, training, and decisions amongst students and teachers with decisions about what students work on based on data and planning.

During PLT a Summit teacher engages in three specific types of activities: classroom monitoring, student mentorship, and targeted small group instruction.

- Classroom Monitoring: The teacher moves quickly around the room glancing over the shoulders of students for a visual check of engagement, quietly redirecting some students when necessary. He circulates around the room between mentoring and small group instruction sessions, checking in on students he knows might be off task. The interactions are brief and positive, often accompanied by encouragement. He connects with students efficiently because he knows each of them well.

- Student Mentorship: At one point the teacher gathers a group of eight students struggling with the most recent history project. “Your important goal right now is to get your grades up in history,” he tells them matter of factly. With his guidance, they spend about five minutes using a graphic organizer to create an action plan where they each (1) identify the specific content where they struggled and some resources they can use to review; (2) schedule office hours with their history teacher for tutoring; and (3) set a date when they aim to retake the assessment. With action plans in place, they return to their seats to begin their review.

- Targeted Small Group Instruction: For the next 15 minutes, the teacher leads a workshop for two students from his math class. “They’re preparing to retake a test, so I’m tutoring them on that. When they’ve shown enough readiness, I’ll be able to release them to do the assessment on their own.” All the while, the teacher scans the room every time the pair of students work on a math problem to monitor the classroom and redirect off-task behavior.

Behind this use of flex time is a myriad of interrelated systems that communicate academic achievement and progress to the teacher, so he knows precisely where each student is relative to their personal academic goals. The teacher can thus facilitate the PLT in a way that is highly data driven and responsive to student needs. Students also have the same access to their own achievement and progress data, empowering students to make informed decisions about how to best use their time. This autonomy is deeply motivating to students. The clear structures and expectations form the boundaries within which students can exercise agency responsibly.

A second interesting example of flex time can be seen at Design Tech High School (d.tech) where students self-schedule their time one day per week.

d.tech Lab Days

Wednesdays are Lab Days at d.tech. Lab Days are student-scheduled days where they plan out their entire day with the guidance of their advisory teacher. On Lab Days, students schedule a combination of lessons based on their needs (including office hours or re-teach lessons with teachers), collaborative work time for class projects with peers, and independent or group work time to explore curiosity projects. Some students work part of the day individually and other parts collaboratively with peers in different workspaces or classrooms throughout the school. Some students spend the entire day in the Design Realization Garage, where they might be working on their robotics team robot or designing and building a cardboard foosball table with friends. For students who are far behind or struggling, Lab Days are scheduled predominantly by their teachers to provide time for intervention and targeted support.

To ensure that all students are making responsible decisions about time, students complete a ‘Lab Coat’ during their advisory class on Tuesday, where they configure their schedule for the next day. On Wednesday morning, students convene again in their advisory class where their advisor returns their approved (and sometimes amended) Lab Day schedules. She asks the students to complete a plan for each part of their day:“What’s your goal and how are you going to reach it?” Students review their plans with each other and head off to follow the schedule on their Lab Coat. Talking to students, it is evident that no matter where we go, about 80-85 percent of the students are engaged and working on what they are supposed to be completing at any given time—more than what you might see in a typical professional work environment.

To truly understand Lab Days at d.tech, you have to go back to the beginning of the school year. In September, d.tech uses a very traditional school day with students traveling to classes together on a regular bell schedule, much like all other high schools in America. Autonomy is created in the classrooms over time by giving students limited but expanding choices on how to learn material (e.g., teacher lecture, videos, articles, etc.) and how to demonstrate what they have learned (assessments, projects, essays, et. al.). Once the administrative team, in consultation with the faculty, determine that students can handle the autonomy, they add a Lab Day into the weekly schedule—with lots of structures, such as the Lab Coats, advisor guidance, and a complex Google Sheet that informs everyone where each and every student should be during each Lab Day block. Once students prove they can stay focused during this single Lab Day, they may add in a second Lab Day per week. In this way, d.tech gradually releases responsibility over to the students and helps guarantee success through well defined systems and structures.

A final example of Flex Time is the Leadership Public Schools (LPS) Navigate Math Program, which is an intervention class for all ninth-graders hosted on the Gooru platform.

Leadership Public Schools Navigate Math

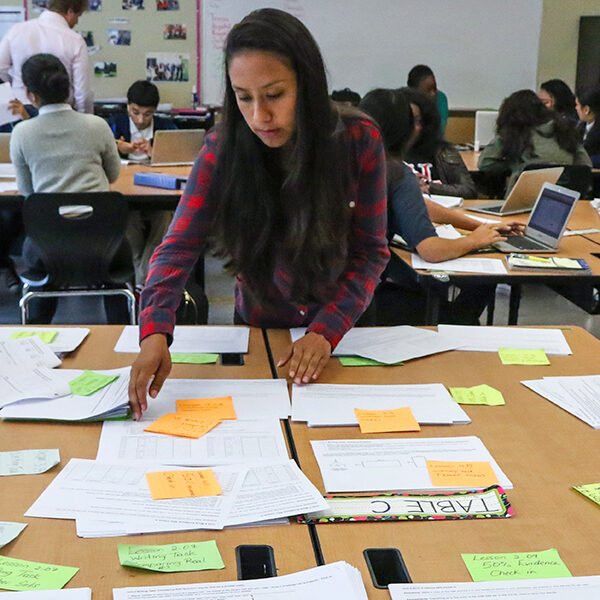

Navigate Math is an asynchronous experience for students designed to fill gaps in math knowledge while also building student skills in agency and autonomy. The first few minutes of any Navigate Math block at LPS have all of the hallmarks of a well-managed traditional classroom. Students immediately commence work through a practiced series of timed opening activities that are mostly teacher led, like a silent ‘Do Now’ and a homework check. Following the homework check, the class begins to morph as the teacher facilitates two more timed activities crucial for building students’ ability to direct their own learning by engaging with goal cycles and setting a daily agenda.

The structure of these opening routines is intentional and designed to gradually transition students from teacher-led learning to a student led block of time where students exercise autonomy in choosing what they work on and how they demonstrate mastery. It can often take several months for students to learn the expectations of the curriculum, how to collaborate with their peers, and how to navigate the digital platform in order to set goals and make decisions about how to most effectively use time and resources.

- Goal Cycles: On their digital dashboard, students set weekly goals that capture what they aim to accomplish for the week, and what they will need to do to meet those goals. Students create a daily agenda that clearly outlines how they will structure their time for the day, including collaboration with classmates or scheduling 1:1 appointments with the teacher.

- Group Collaboration: In small teams, students assume group work roles for the month. Along with the specified tasks of that role, students focus on developing specific team norms, like active listening or engaging in focused academic conversations. The norms and the roles ensure that each student understands his or her responsibilities to the group, increasing motivation through peer accountability.

By being so deliberate in how they teach students to approach self-direction, the teachers at LPS set their students up for success. Despite knowing the value of student ownership, teachers are careful not to release students to self-direction without first ensuring they know how to make responsible data driven decisions, how to manage their own time, and how to maximize use of the available resources including their peers and teachers. As those habits become established, each of the routines that began as teacher-led gradually become student-driven.

For a deeper look at LPS’s model, visit TLA’s school model profile.

These school examples share many of the traits in common we identified up above as key ideas for successful implementation of flex time. Our most significant discovery is that each school gradually released agency for decision making to the students, starting very tight in the fall and then loosening up throughout the year as students demonstrated the necessary habits and practices. The schools invested considerable time in explicitly teaching students how to be successful when working more independently, and giving students the opportunity to practice this under direct supervision before doing it on their own. But releasing control to the students did not mean releasing responsibility by the teachers; these schools vigilantly maintained systems and structures to monitor and check-in on how well students used their agency to ensure adequate learning was still happening.

Flex time succeeds when schools foster autonomy through systems, structures and protocols. These systems are often behind the scenes and hard to see at first glance. Visitors to a successful flex time period see the final destination without understanding the arduous journey it took to get there. We hope that through the narratives of these three schools you can begin to peek behind the curtain of what it takes to successfully support student agency through flex time.

Opinions presented in this blog post are those of the author and do not necessarily represent TLA’s opinion, nor should be considered an endorsement by TLA of any organization or product.