This blog first appeared on EdWeek’s Next Gen Learning in Action column.

With all the interest in innovative school models, many schools are creating “flex time” periods during the day for students to increase student agency. We at Silicon Schools Fund and Relay Graduate School of Education set out to understand what makes flex time periods work best and started with a deep dive studying and writing about the topic.

The idea behind flex time is that students can build the skills to work effectively on their own and that by allowing more choice and freedom, students will be more engaged in their learning. In successful schools we did observe students exhibiting agency and working quite independently, which raised the question, “how did these classes reach this place of success?” When talking to these schools, they suggested that it worked best to begin with more teacher-directed systems and structures and then gradually transfer responsibilities onto students as they demonstrate readiness. The school support structures begin in the foreground and gradually fade into the background.

The end result is that when educators visit these successful implementations of flex time, they often can’t see the work behind the scenes that went into making the schools successful. Because the finished product is smooth and students and teachers know their roles, it can make flex time look easy. When others try to replicate, they mistakenly jump into a late-stage version of flex time, where students have lots of autonomy and forget to build up the systems that support such freedoms. This article seeks to look behind the curtain and share how successful schools designed and launched great flex time periods that ultimately slowly release students to real autonomy.

Getting to Great Flex Time

We’ve seen schools go through four steps on their path towards great flex time. These stages are not distinct, but rather work in concert with each other. Like when a child learns to swim, she first puts her face in the water, then blows bubbles, then starts to kick, and then adds arm strokes. When done all together, she is successfully swimming. Like almost everything in education, the first step in creating flex time is setting the classroom culture.

Stage I: Set the Classroom Culture

To get to eventual freedom and agency, teachers begin with explicit classroom culture and procedures. These classrooms are much more teacher-driven at the start. Students learn how to come to attention when asked by the teacher and how to work quietly – essential elements of pretty much any effective classroom. Students also learn how to ask for help, what to do when they are stuck, and how to productively work in small groups. In this early stage, teachers are building trust and connection between student-to-teacher and student-to-student. Once the norms and procedures for a tight classroom are in place and once positive relationships fuel the culture, the classroom has the necessary ingredients to enable the coaching, feedback, and peer-to-peer collaboration to come that is necessary to move towards a more student-directed approach.

The most effective teachers we observed narrate some of this journey to students, explaining where the class is headed and how the systems they are practicing will give way to much more student autonomy. As classrooms move to more flexible time for students to manage on their own, we see some specific teacher moves working to support this autonomy:

Strong Whole Class Openings:

When a flex time period begins, the teacher can spend a few minutes setting the tone for the class, having students create a learning target, reminding students of what they are working on, and focusing on any habits or behaviors that might need a refresher. Openings provide an opportunity to set clear expectations and to practice important procedures as well as provide a strong daily culture reset to ensure students maximize their work time once they start independent work.

Effective Monitoring:

During a flex time period, great teachers make it clear to students that time is sacred and that students should use their freedom wisely. Teachers model engagement by actively circulating the room, conferring with students 1:1 or in targeted small groups, and actively keeping an eye on students to help nudge them back to productivity when needed. These teachers maintain such monitoring even while performing other tasks such as conferencing and small group instruction.

Purposeful Use of Pen and Paper:

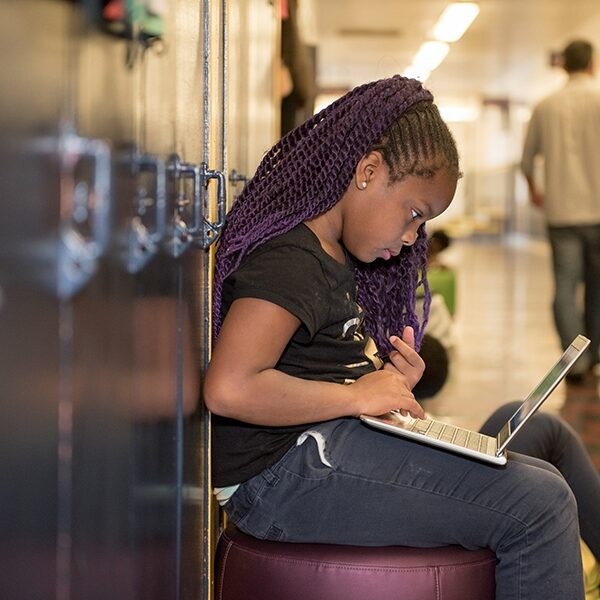

During flex time, students often use laptops or tablets to learn content or produce products. Even when using digital mediums, we’ve seen teachers successfully implement a paper-based system to support the learning that is happening online. Some teachers like to have students record notes on paper (even if the material is on a screen) believing in the power of manually writing to help cement learning. Other teachers like the paper record as evidence of what students have learned and a quick way to touch base with students on progress when circulating a room. Some teachers really like students setting goals on paper and tracking their progress physically (see more below). As we give students more freedom we want to trust them to make good decisions, but we also want to implement systems to keep them engaged and accountable.

Strong Whole Class Closings:

Much like a whole class launch at the beginning of class can be powerful, we are believers in whole class conclusions. Teachers can ask students to reflect on their own productivity during the class, reinforce noteworthy effort or progress, and remind students of elements they want to keep students focused on. The learning may mostly be independent during a flex time period, but the social nature of groups makes us believers in the power of still launching and concluding briefly together as a class.

Stage II: Developing Good Habits

Once students understand the expectations and systems for independent work time, teachers can begin to teach students the habits required to successfully make the most out of flex time. Setting clear goals, reflecting on progress, making good choices, and students monitoring their own use of time and energy are key habits to be taught and practiced.

Goal Setting and Progress Monitoring: Early on, teachers often set goals for students, usually related to progress over a set amount of time. Teachers often have students record their goals in a graphic organizer and track progress. Eventually the teacher can have students practice setting their own goals, thereby increasing buy-in. Most students are not used to daily or weekly goal setting and will need some support, which is why teachers build in time to model good goals, ensure students are accurately tracking progress, and improve students’ ability to figure out what they most need to work on. Teachers often begin 1:1 check-ins (see below) by reviewing and reflecting on student goals.

Modeling and Reinforcement: Teachers need to help students learn the habits of self-directed learning like what to do when stuck, how to use a learning platform or other online resources, and what to do when distracted or when energy wanes. Teachers often focus on a single learning habit for a stretch of time until it can be consistently demonstrated by students – such as note-taking, help seeking, or studying. Leveraging the whole group opener to model ideal behavior can be effective, as well as having students reflect on how well they accomplished their focus at the end of class. During class time in a flex period, teachers watch for the desired actions, sometimes narrating examples, and offering precise praise when practiced effectively.

Stage III: Release and Catch

As students start to show more readiness for independence and small group work, educators have to do the hard step of really letting go. Like the moment when a child leaves the comfort of the swimming pool wall and ventures into the deep end, students need the chance to put everything together and figure out how to use a period of time effectively on their own. By that point (based on previous positive reinforcement and redirection), students should know exactly what is expected of them, have strategies to be successful, and have formed trusting relationships with each other and the adults in the room. The teacher works to intentionally build the stamina of students to sustain their own learning for longer periods of time. At this point, we encourage teachers to sparingly interrupt the class, instead addressing any issues with individual students to let the learners experience what it’s like to have uninterrupted time to direct their own learning.

While students are working independently, teachers sometimes are left wondering, “What do I do?” We’ve seen too many teachers revert to wandering the room, addressing each hand that comes up. Instead, some of the best teachers realize that they are now free to engage in some of the highest impact teaching time in the form of 1:1 check-ins and small group instruction.

1:1 Check-ins: Gradually increasing student autonomy frees teachers up for more targeted individualized support. Using data from formative assessments, observations, and student reflections, teachers start to plan 1:1 check-ins with each student at least twice per month. During these 3-10 min interactions, teachers confer with students to deepen relationships, provide coaching on specific cognitive habits, and offer brief content interventions. This is a great time to reflect on student-created goals, help students improve their ability to assess their own progress, and target support to the students who need the most support for remediation or a chance to push further for high-achieving students.

Small Group Instruction: Some of the best teaching in flex time settings comes in the form of teachers pulling targeted groups of students to sit around a kidney shaped table and get a targeted mini-lesson that is “just-in-time” to support a challenging concept or practice a difficult skill. Teachers obviously have to monitor learning to know when students are ready for such small group instruction, and lessons have to be well-planned and shorter duration to be most effective.

Destination: Student Drivers

The goal with flex time is to eventually get students to be able to make good decisions to:

- Figure out what they need to work on

- Prioritize their work

- Set clear targets

- Work efficiently and independently

Think back to the most earnest of your friends in college and how they worked when in the library independently. If this is the end state of student-driven learning, what is reasonable to expect for elementary, middle, or high school students? Likely the intermediary step is something akin to student drivers – where learners get full control of the steering wheel and gas pedal, but still have a trusted guide in the car just in case.

In this final stage of student self-driven learning, students make most of the decisions. The teacher, however, still explicitly develops classroom culture and trusting relationships with whole class, small group, and individual activities. Students may be exposed to more advanced cognitive habits and tools that promote agency and academic development.

Student-Led Goal Cycle and Daily Agenda: Goal setting during this stage becomes increasingly student driven. Students exercise increased ownership by setting ambitious goals for themselves over longer periods of time. Students identify the strategies and resources they will need to accomplish their goals and tracking their progress towards completion. Creating a daily or weekly agenda allows students to manage their own time during the period and gives teachers an easy way to quickly know what each student should be working on.

As classrooms evolve from one stage of self-directed learning to the next, students gain more and more agency and autonomy over their learning. But to reiterate, in almost every case where this desired state of independence and freedom is reached, schools started off much more tightly controlled and gradually supported students to take on more agency. The big shift is the systems, structures, and routines that started out teacher driven and can gradually fade into the background as they are internalized by students.

We believe that flex time can both effectively help students learn content and support their development of skills that will prove powerful throughout a lifetime. As one student said recently about their flex time classroom, “I thought this time was just for doing more math, but now I am using the strategies I learned in this class in all of my other classes and I know it will help me in college.”

If you are interested in learning more about flex time and are interested in piloting supports for teachers in implementing the moves necessary to be effective, please reach out to Jeff Starr at Relay Graduate School of Education (jstarr@relay.edu).