We’re often asked to explain how virtual learning outcomes compare to those in traditional, analog classrooms. This is a fairly straightforward question to answer based on research: generally speaking (and outside of emergency models launched during global crisis), virtual experiences have been found to be as good as in-person ones. Additional evidence suggests that blending virtual and offline approaches might produce better outcomes. (Means et al, 2013) In other words, outcomes aren’t a function of modality but rather the quality of design and implementation (a topic we’ll be addressing later in this series).

However, the question of comparison – whether virtual learning can successfully replicate traditional classrooms – is likely missing a critical point. Our standard models aren’t really serving students well, especially for those historically and systematically underserved. When we know that this bar is already failing so many, the right question isn’t “how well can virtual learning replicate in-person learning” but rather “why might we pursue virtual learning to help us work in new ways to produce better outcomes for students?”

In our work over the last year, TLA has been talking to students, families, educators, and other community members across the sector to try to understand what new value they’d want from virtual models. As we’ve profiled existing schools and worked with districts and state teams across the country, we’ve also witnessed the ways educators and learners are using virtual learning tools to solve problems they couldn’t before.

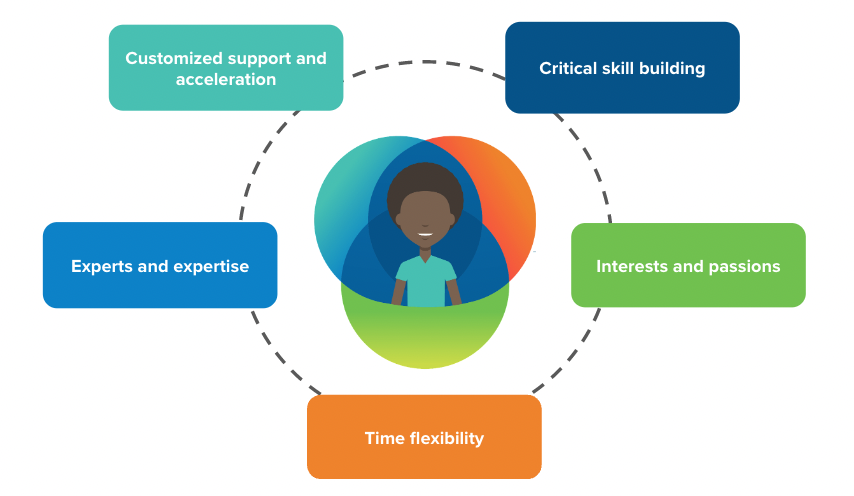

These conversations and observations surfaced a lot of potential “whys” for the work. Which improved or new outcomes should we seek? From our view, here are five aims worth pursuing:

-

Customized support and acceleration. As educators work to address unfinished learning, virtual tools and programs, such as the Khan Academy and NWEA’s MAP Accelerator, offer ways to support independent practice targeting individual skills. Schools are increasingly tapping into virtual tutors and mentoring programs, as well as using virtual means to ensure access to critical interventionists, such as in Cudahy, WI where reading specialists work across campuses to reach more students. In other cases, teams have established virtual office hours, which help students problem-solve and stay on track.

-

Access to experts and expertise. In a moment when schools are navigating talent challenges, virtual learning can help us connect learners to the experts they might not have access to in their building (due to vacancy or competing demands). Districts, like Meriden, CT, in partnership with the National Educational Equity Lab, are offering course access to offer experiences not available locally and/or build college credit. Schools are also creating new roles, like learning coaches focused on building skills for self-direction and social-emotional development. Learners are also able to tap into specialists working outside of K-12, such as scientists working in the field.

-

Tapping into interests and passions. Learning virtually outside of school hours can create more time for hands-on activities, projects, and meaningful career learning (such as internships). Educators can also create authentic experiences with families off campus. Systems are also partnering with entities like Stepmojo to increase access to high-interest electives.

-

Using time more flexibly and efficiently. Time is perhaps our most precious resource for learners and educators. Educators have long been using virtual tools in a “centers” approach (sometimes called a “station rotation model”), which can free up teacher time to offer more one-on-one and small-group instruction. Adopting hybrid models, or letting students tap into learning experiences outside of school hours, can also help learners who may need the flexibility to take on jobs or take care of younger siblings and children. At the height of COVID, one superintendent reflected to us that remote learning had a profound, positive effect on school attendance and truancy reduction. He noted that, especially for students with significant responsibilities at home, being able to log-in to class from home helped. In a world where some students report spending four hours commuting to school each day (negatively impacting sleep and exercise), how might hybrid or virtual schedules help?

-

Building critical skills for the future. Innovators like STEMuli, in partnership with Dallas ISD, are building virtual environments that allow students to gain meaningful career and technical education experiences they wouldn’t be able to access in local environments. Further, working across boundaries through digital means is becoming a new workforce norm, be it through collaborating with colleagues across offices, tapping into online professional learning, or working remotely. Experts point to a future (arguably, already here) that will increasingly demand digital competence (as well as skill gaps that begin early on). How might engaging in virtual learning — in supported and safe ways — allow students to begin building the type of skills for self-direction, digital citizenship and literacy, and communication necessary to successfully navigate their future jobs, relationships, and civic participation?

Given this universe of different opportunities, it’s critical communities identify their own “why” for virtual learning. How might they do it? In our work with our Strategy Lab school systems, we always begin with equity asking systems to reflect on the problems that feel most intractable within the current confines of resources and practices. By focusing on those learners least well-served within those confines, we can ask how virtual learning might help.

This post was the third in a series on virtual and hybrid learning policy, so stay tuned for more to come. The first blog explored what TLA is learning about virtual learning. Have a learning or idea about virtual learning you’d like to share? We’d love to hear from you! @LearningAccel