Given our lack of unified language, conversations about virtual learning often feel confusing. Is my district’s “hybrid” learning your school’s “simultaneous” instruction? Has one state codified policy for “blended learning” in a way that looks a whole lot different from what its schools and districts have been implementing in classrooms for the last decade?

Lack of clarity around models and terminology is certainly not a new challenge for the education sector, but the pandemic accelerated awareness and adoption of new terms at an unprecedented rate, with little coordination or norming. As we seek to move beyond the chaos, it’s critical we start getting aligned to build common understanding and evidence. Doing this will require consistent language with shared definitions.

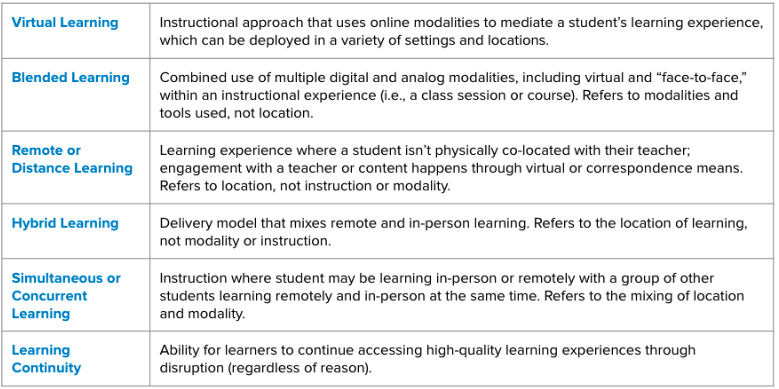

The Learning Accelerator (TLA) has been working to refine our language and understanding of virtual learning so that we can have better, clearer conversations about it, how it connects to goals for students, and how it can work in practice. Which terms might we use, and how might we arrive at them?

At TLA, we hold two principles when choosing language to describe approaches and strategies:

- Prioritize the learner and their experience in learning. We shouldn’t elevate language that centers on adult systems of organizing or fails to get us all to the level of specificity we need to improve learning. For example, this is why TLA chooses to use the term “unfinished learning” over “learning loss” to describe students’ experience in the pandemic. Learning loss prioritizes a system-level expectation to produce hypothetical growth across a very heterogeneous group of students. From a practical perspective, it’s relatively useless. Which students lost what? Why and how? Did they have “it” to begin with? It’s much more useful to ask what concepts and skills a student had an opportunity to be exposed to, whether or not they mastered them, and if not, how to support that unfinished progress.

- Don’t confuse definition with vision. Our sector often layers on qualitative distinctions and modifiers, conflating the “what” with the “why” and “how.” For example, I recently read a blog post in which the author defined a specific learning strategy as “an approach that empowers every student at every level to progress with confidence.” That’s a hope, not a clear definition, and a pretty subjective one at that. Our definitions should help us talk about the “what” in relation to quality and outcomes.

Given these principles, here’s our working definition: Virtual learning is an experience where online modalities mediate a student’s interactions with learning content and their teacher.

Using this definition, virtual learning…

|

Thinking this all through has helped us get consistent and better understand which types of virtual learning models schools are pursuing and why, especially as we engage with schools in different communities. We’re still refining and pressure testing, and we know we’ll keep learning over time, but we hope this is helpful to those communities working to formulate common definitions and understanding that can help them move forward in their context. Centering the learner experience and how virtual learning is working to mediate it is a good starting point.

This post was the second in a series on virtual and hybrid learning policy, so stay tuned for more to come. The first blog explored what TLA is learning about virtual learning. Have a learning or idea about virtual learning you’d like to share? We’d love to hear from you! @LearningAccel