Imagine someone asked you to measure the weight of a bowling ball using only a ruler. You could measure the diameter, calculate the volume, and then estimate the weight based on historical averages. Or, you could use a scale.

Now consider another example. What if you had to evaluate the quality of a track and field team that includes sprinters, jumpers, throwers, and distance runners, but the only two measures could be time on a mile run and number of consecutive pushups? Some athletes would excel on one or both of those measures, but a more accurate approach would include a constellation of assessments to understand various strengths.

Unfortunately, we often apply the strategies described above when trying to understand the effectiveness of different educational models. Students are treated like bowling balls, weighed primarily with rulers. Schools – though acknowledged as having a diversity of students similar to a track team – have their efficacy assessed primarily with two tools: English Language Arts (ELA) and math proficiency scores. Particularly with more innovative school models, relying solely on these measures is as reasonable as using only pushups and mile times.

Breaking the Quantitative Fallacy

Education has long fallen victim to McNamara’s Fallacy – the tendency to focus on what can be measured easily (i.e., ELA and math scores) rather than what might be more difficult but also more appropriate. This challenge became salient as we recently conducted a landscape scan of 64 fully virtual and hybrid public school models.

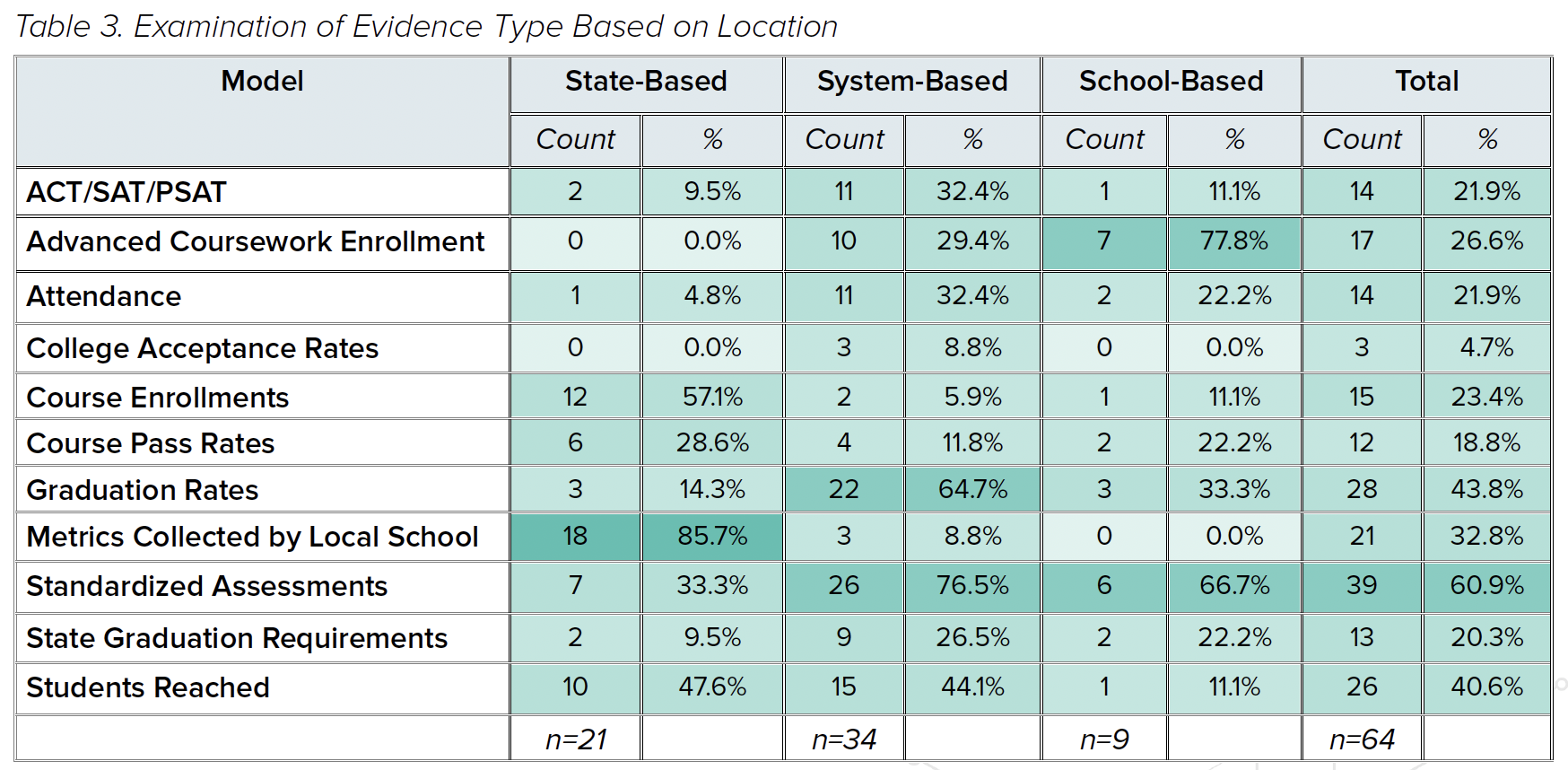

In our analysis, as we sought to identify evidence of success, we found a variety of measures depending on the context:

-

State-level virtual schools such as Montana Digital Academy reported metrics like course completion and number of students served;

-

Fully virtual and hybrid schools that exist inside either traditional K-12 districts or charter systems typically included attendance rates, course grades, and progress against standards; and

-

Some models like Valor Preparatory Academy also cited performance-based assessments such as projects completed or public demonstrations of learning.

Looking across all of the schools and systems in our scan, no single common measure emerged. In fact, we identified a constellation of evidence that included BOTH traditional assessments AND performance-based measures like portfolio reviews or student-led conferences. Coming back to McNamara, thinking that we could use a single quantitative measure to understand fully virtual and hybrid models would be as inappropriate as assessing an entire track team based on their mile times.

The N/0 Paradox

When interviewing virtual and hybrid school leaders, we uncovered an even more critical concept influencing measurement: many of those models, by design, create learning opportunities for students that might not otherwise have existed. Consider a student who gains access to an AP course via a virtual or hybrid model that did not exist in their local brick-and-mortar school, a learner who stays enrolled in their local district through a virtual option when they cannot physically attend school because of illness, or a student who was previously chronically absent but now attends online because it fits their schedule better.

In the scenarios above, those students could engage in learning where previously nothing existed. As one leader explained, “these kids wouldn’t be learning anything if they were not enrolled in the [virtual] program.” Much like how it is impossible to divide a number by zero, “effectiveness” needs to account for the fact that without the fully virtual or hybrid model, NO schooling would have occurred. In other words, we cannot divide something by nothing and then make a conclusion.

During the 2024-25 school year, we will be conducting a deep-dive study with six fully virtual or hybrid models to deeply understand how they are working for different students and in diverse contexts. Many of these students have been failed by the traditional, brick-and-mortar system, lacking course access, individualized pathways, flexible schedules, and personalized support. By taking a both/and approach, and observing a constellation of evidence in addition to traditional measures, we will be able to measure efficacy in a more holistic way.

Read the full report: “Where, Why, How: Deepening Analysis of the U.S. K-12 Virtual Learning Landscape,” here.